There are more than 100 million lakes dotting the planet, according to one prominent study.

But many aren’t what they used to be. From Bolivia to South Africa and beyond, climate change, pollution and over-abstraction are drastically changing these bodies of water. Many have dwindled to nothing. Others are bursting their banks. Some have even turned green.

“Today, some of the world’s best-known and most important lakes are a shadow of what they were just a few decades ago,” says Dianna Kopansky, the head of the Freshwater Ecosystems and Wetlands Unit of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). “We need to reverse this decline. If we don’t, it could be calamitous for the hundreds of millions of people who rely on lakes for their survival.”

Ahead of the first World Lake Day, observed on Wednesday, August 27, 2025, here’s a closer look at the biggest threats to the world’s lakes – and what can be done about them.

Climate Change

A global panel of climate experts has found that climate change is destabilising the hydrological cycle, the finely tuned system that distributes water around the world. Rising temperatures, they say, is intensifying evaporation and shifting rainfall patterns. In some places this is increasing the chances of lake-shrinking droughts, like one that nearly deprived Cape Town, South Africa – home to 4.7 million people – of water.

In other places, increased evaporation coupled with higher air temperatures is leading to more intense rainstorms, causing lakes to burst their banks. That’s a future that may even befall the world’s largest desert basin, Kenya’s Lake Turkana. A UNEP study found it will likely see an increase in flooding in the coming decades, threatening the 15 million people who live along its shore.

Meanwhile, in many mountainous areas, skyrocketing temperatures are raising the risks of what are known as glacial-lake outbursts. These potentially catastrophic floods can happen when the ice holding back a lake melts, sending water cascading downhill.

Over-abstraction

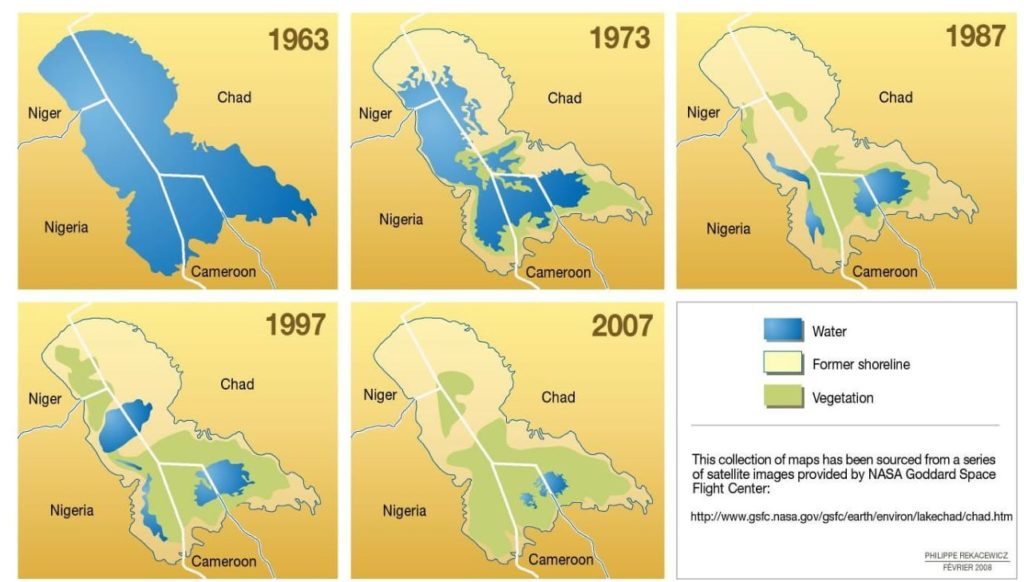

As damaging as climate change has been, Kopansky says it often pales in comparison to what humans have done to lakes by siphoning away their waters faster than they can be replenished – a process known as over-abstraction.

This can take many forms. Sometimes, water is diverted from lakes – and equally damaging, their tributaries – to supply cities. Other times, it’s used to power hydroelectric dams. Often, it’s taken to irrigate farmland.

Central Asia’s Aral Sea is the poster child for irrigation-led decline; once the fourth-largest lake in the world, has withered dramatically since its tributaries were diverted in the 1960s. But this is happening all over the world, including in the high plains of Bolivia. Here, what was once the country’s second-largest lake, Lake Poopo, has been reduced to a barren salt flat by a devastating combination of water diversions and climate change.

A 2024 report by UNEP and UN-Water found that surface water bodies, including lakes, are shrinking or being lost entirely in 364 basins worldwide – nearly 3 per cent of all basins. An estimated 93.1 million people live in those areas.

Pollution

Pollution, experts say, is a mounting threat to the world’s lakes and the communities that surround them. Especially problematic for people and lake-dwelling animals are raw sewage and farm runoff. Along with injecting pathogens and pesticides into lakes, these sources of pollution also often contain phosphorus and nitrogen. At high enough levels, these nutrients can kill fish, feed toxic algal blooms and starve lakes of oxygen, creating so-called dead zones hostile to aquatic life.

That’s what some scientists believe may be happening in Lake Victoria, Africa’s biggest lake, where a surge in a certain type of bacteria has turned waters green.

At the same time, increased evaporation, over-abstraction, rising precipitation and hotter temperatures can also worsen water quality.

UNEP tracks the water quality of 4,000 large lakes around the world. More than one-quarter are becoming increasingly turbid, or cloudy, and almost 15 per cent are experiencing a rise in organic matter. Those are two telltale signs of pollution from sources like cities, farms and factories.

“These kinds of numbers should be a wakeup call,” says Kopansky. “We can’t continue to treat lakes like dumping grounds.”

The solutions

Lakes provide 90 per cent of the world’s surface fresh water and, together with the rivers that feed them, support the livelihoods of an estimated 60 million people. Kopansky says it’s not too late to reverse the fortunes of many of the world’s flagging lakes. To do that, she says countries can do three major things:

- Advance what’s known as integrated water resources management, a planning process that balances the use of water across various sectors, like industry and farming, in ways that improve lives without compromising the long-term health of ecosystems;

- Take a basin-level approach to water management and pollution control, involving local and Indigenous groups, the private sector, farmers and other stakeholders to address the challenges facing lakes; and

- Invest in data collection monitoring for lakes and invest in applying it, so that problems like pollution can be caught before they reach crisis levels.

Protecting the world’s lakes is a key part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, an international agreement to safeguard the natural world. The accord calls on countries to conserve and restore 30 per cent of inland waters, which includes lakes, by 2030.

“The good news is that we have the knowledge and the technology to turn this situation around,” says Kopansky. “What we really need is the will to start treating all our lakes like the precious resources they are.”