One of the key outcomes of the Second African Conference on Agricultural Technologies (ACAT2025), held in Kigali, Rwanda, in June 2025, was a timely reminder to African governments and people that the continent has a shared vision and aspirations it is pursuing: “The Africa We Want – Agenda 2063.” This 50-year blueprint developed in 2013, serves as the continent’s master plan for sustainable development and economic growth.

Aspiration 1 of Agenda 2063 envisions “a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development,” with the goal of achieving zero hunger. Realising this aspiration, according to the Acting Head of the Genome Editing Programme at the African Union Development Agency-NEPAD (AUDA-NEPAD), Prof. Olalekan Akinbo, “hinges on the core pillars of policy, science, and community engagement, supported by appropriate science communication.”

Communicating science within the political space

Speaking at one of the sessions during the ACAT2025, he emphasised the importance of communicating science “in a way that is understandable and actionable for policymakers.

In a subsequent interview, Prof. Akinbo elaborated: “Communicating science within political spaces is absolutely critical and must be done with an understanding of the dynamics involved in presenting scientific information to non-scientists, particularly those with political interests.”

He noted that the focus of such communication should include “demystifying scientific technology and innovation, and deepening understanding of the role science plays in national development.”

As an agency mandated to support the development and implementation of science-related policy across African Union member states, AUDA-NEPAD, Prof. Akinbo said, insists that science communication must be grounded in national science policies and aligned with the broader continental agenda.

“The African Union works through existing national structures,” he explained. “For instance, scientific institutions are mandated to generate research outputs that reflect government priorities, especially where those institutions receive state funding. These innovations, such as improved crop varieties, must be aligned with national development goals.”

Prof. Akinbo added that effective science communication must involve national structures, such as scientists working directly on technologies of strategic interest to government. He emphasized the importance of highlighting the role of government and its financial commitment to research aimed at reducing poverty and improving livelihoods.

“To ensure impact and sustainability, policymakers’ interests must be aligned with continental science and innovation policies. Otherwise, there’s a risk that local political interests may overshadow or derail broader development goals,” he concluded.

Embracing biotechnology in Africa’s agriculture: The urgency of now

In a related development, the founding Director of the West Africa Centre for Crop Improvement (WACCI) at the University of Ghana, Prof. Eric Yirenkyi Danquah, issued a strong call to action:

“Unless African leaders act boldly to transform the continent’s agriculture, we will continue to fail our people.”

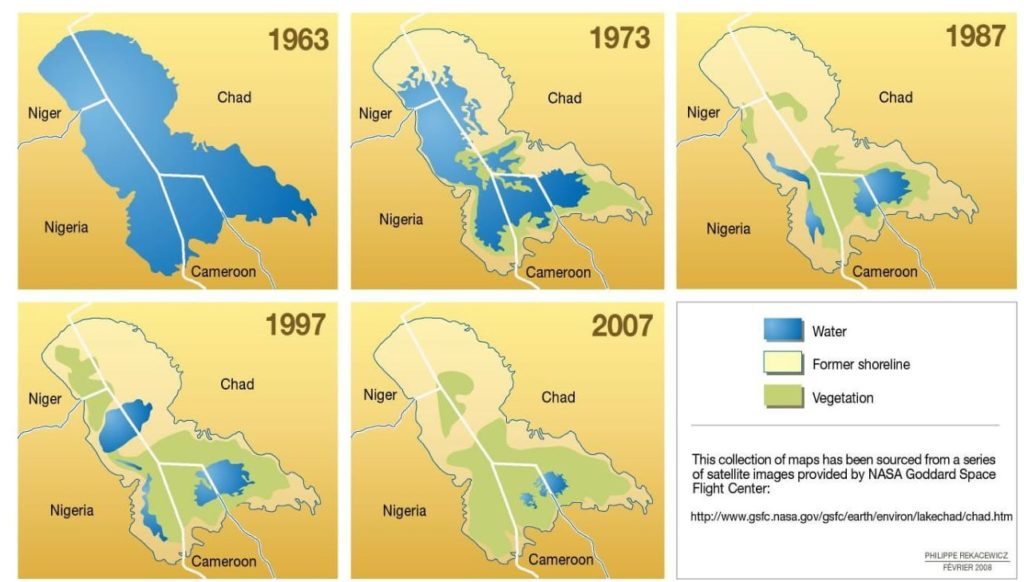

Speaking at a regional stakeholders’ meeting in Accra on agricultural biotechnology in Africa, Prof. Danquah underscored the immense pressure Africa’s agriculture is currently under: from climate change, food insecurity and population growth to limited access to new technologies.

“Biotechnology offers us real hope,” he stated. While acknowledging that biotechnology is not a magic bullet, he emphasised: “…it is a powerful tool – one that allows us to develop better crops faster, to feed growing populations, and to build resilience against the shocks of climate change.”

He continued: “If we embrace it with wisdom and courage, we can change the story of hunger in Africa. But to truly unlock the power of science for the good of all, we must also confront deeper issues of justice, the need for evidence-based action, and the urgency of now”.

That urgency is underscored by rapid population growth across Africa. Ghana, for example, is projected to increase hers by over 2.25 million people within the next five years. This population surge highlights the critical need for new breeding tools that deliver resilient, nutritious, and high-yielding crops to ensure food security.

Prof. Danquah stressed that finding sustainable solutions to improve agricultural productivity and resilience is non-negotiable and the role of biotechnology in this endeavor cannot be overstated.

While commending Ghana’s progress, including the historic approval of genetically modified (GM) Pod Borer Resistant (PBR) cowpea in July 2024, exactly a year ago, he acknowledged that barriers remain. “These approvals demonstrate our cautious but steady approach to adopting biotechnology, carefully balancing innovation with available resources.”

To fully realise the benefits of biotechnology, Prof. Danquah emphasised the need to strengthen and scale up research and regulatory institutions. “Without this, the impact of innovation will be limited, and our ability to respond to future challenges will be compromised,” he warned.

One of the issues that Africa needs to tackle to strengthen it agricultural sector is the development of the required human capital.

Building Africa’s next generation of plant scientists

In Ghana, some key academic institutions are already training students in the tools of scientific technology and innovation adoptable for agricultural purposes. WACCI is one such institution. Since its establishment in 2007, the Centre has been at the forefront of efforts to transform agriculture in Africa through enhancing the capacity of human capital. The Centre is training the next generation of African plant breeders – for Africa, in Africa.

So far, WACCI has graduated over 120 PhDs and 60 MPhil holders, many of whom are leading agricultural innovation across 15 African countries. In Ghana alone, 28 of the Centre’s plant breeders including Prof. Maxwell Asante, Director of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research-Crop Research Institute (CSIR-CRI) at Fumesua, near Kumasi, and his Deputy, Dr. Ernest Baafi are WACCI alumni. At the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Institute-Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (CSIR-SARI) in Nyankpala, near Tamale, Dr. Joseph Adjebeng-Danquah, another WACCI-trained scientist, serves as Deputy Director.

Together, WACCI alumni have developed and released more than 290 improved crop varieties now in the hands of farmers across the continent. In addition, WACCI and its graduates have attracted over $100 million in funding to support agricultural research and development activities in Africa.

By Ama Kudom-Agyemang