“Water is life’s matter and matrix, mother and medium. There is no life without water.” – Albert Szent- Gyorgyi, 1893-1986

The Lagos Water Corporation (LWC) is a government-owned corporation that has poor performance ratings among the city’s large population. For the greater part of its establishment, it has been unable to meet its daily water production target required to meet the needs of all Lagos State residents for domestic use and general sanitation purposes.

From historical recollection in The PUNCH editorial of August 15, 2025, “… the state’s public water, inaugurated in 1910, provided an optimal water supply until the 1970s; the infrastructure has since deteriorated amid rapid population growth in Nigeria’s economic hub.” Sadly, as we write, the situation has deteriorated further and is daunting.

Since 1970, when the performance of the LWC began to deteriorate rapidly, the various efforts made to mitigate the decline in service delivery have been less impactful. While demand for potable water increased exponentially, planning in terms of need projections and extension of additional water production plants was at a snail’s pace. In addition to these foundational challenges, there was the major issue of outdated and overused water infrastructure/equipment, which hampered smooth production and uninterrupted distribution of potable water supply to the public. Hence, a daily target production has never been met to date.

Based on the current estimate, “Lagos needs 700 million gallons of potable water supply daily to sufficiently cater for over 20 million residents. However, the LWC supplies a dismal quantity of 200 million gallons per day, leaving a deficit gap of 500 million gallons per day.”

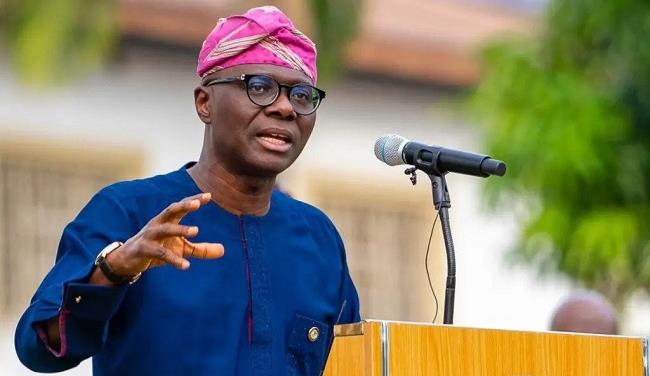

At a Water Conference held in Lagos in 2024, the incumbent governor of Lagos State, Babajide Sanwo-olu, admitted that “the state had invested heavily in capacity building, international partnerships, and stakeholder engagement without commensurate outcomes in the water sector.”

This is a clear example of an effort in futility, as the government was consistently doing the same thing all over again and expecting a different result. If the Lagos State Government does not embrace time-tested policies and a multi-faceted/best practice approach to enhance the provision of potable water supply to the huge population of the megacity region, the LWC will continue to be what it is: a laggard water service provider.

What is exactly being done wrong by the water supplier corporation?

Firstly, the LWC is still living in the past, acting like a one-way organisation. It is neither proactive, explorative, nor innovative. The Management is sluggish and often reluctant to explore any other sources of modern water treatment through the conversion of seawater to potable water (desalination), despite the inexhaustible and ubiquitous sources of seawater available in the state.

The megacity is a coastal city surrounded by two large water bodies, the lagoon and the Atlantic Ocean. That is an advantage that the LWC ought to leverage to the fullest, rather than its sole reliance on the Ogun and Owo rivers for its untreated water sources. Unfortunately, the two river sources are not reliable, hence, not adequate and sustainable for the water needs of the state’s large population. The LWC should change its strategy in this regard. There is no concrete evidence that the LWC has embraced this sophisticated technology for an efficient and reliable source of water supply.

The desalination technology is not rocket science. It is the process of removing salt and other minerals from seawater to produce freshwater that is suitable for human consumption. Most countries/cities have embraced the technology where it is feasible, especially in coastal areas. For example, the Department of Water Management purifies water from Lake Michigan to meet its daily requirement of 750 million gallons of potable water to Chicago and 126 suburban communities. In Israel, desalination is commonly practised to produce urban water for the citizens.” (World Bank report, 2015) “Cairo, the capital of Egypt, sources its potable water from the Nile River, which provides about 90% of Egypt’s total resources.”

The current strategy by the LWC cannot yield meaningful and impactful results in light of the increasing demand for drinking water among Lagos residents. Therefore, the time for the LWC to embrace the desalination technology is now! Let the advanced water treatment be replicated in Lagos to meet the daily production target estimated at 700 million gallons per day. International cooperation, including city-to-city cooperation, is both necessary and mutually beneficial in promoting the livable cities agenda across the world.

Secondly, global experts in public water management have repeatedly advised the LASG to review its often-muted water privatisation policy and to jettison the idea of Public-Private Partnership (PPP). Why? Because examples abound that the model has been a colossal failure. Empirical studies found that proponents of water privatisation are “smooth talkers.” They made lofty performance promises they seldom fulfill. Again, the notion of private sector efficiency had also been debunked.

We suggest that the recent proposal by the LWC be reconsidered. The PPP option for water delivery service in Lagos is unsettling to members of the public and Water Aid advocates, who cautioned in a previous report on the same subject matter that, “while the World Bank has spent millions of dollars pushing PPPs and other forms of privatisation in Lagos, the state’s water crisis has only worsened.

“And that, ….PPPs have repeatedly failed to provide the needed investment and have led to skyrocketing rates (at the expense of consumers), job cuts, and other anti-people practices.” With such “clarity of admonition,” one is curious to ask the pertinent question: why does the LASG want to tread the same path of failure?

The views expressed by Mr. Rotimi Akodu, Special Adviser, Ministry for the Environment and Water Resources (at the August 14, 2025, stakeholders meeting), that “…operational efficiency-elements could be enhanced through strategic PPP,” call for caution if Nigeria’s experience with the privatisation of the energy sector is a pointer. That is a bitter story to tell for another day.

The management of public water provision is better handled by governmental institutions, as is practiced successfully in other climes. The City of Chicago’s Department of Water Management (DoWM) is solely responsible for purifying and delivering potable water to residents of Chicago and numerous surrounding suburban communities, uninterrupted. The key responsibilities include the purification of water obtained from Lake Michigan, treating it to meet the standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA).

The department manages the water infrastructure distribution system, including tunnels and a gamut of purification plants that serve the city. This situation is obtainable in many American, African, and European cities. Most state and municipal governments, as a matter of public policy, do not privatise public water supply, and their departments of water management are run efficiently by competent administrators, managers, water engineers, and allied middle cadre technical staffers who add value to their daily tasks.

On finance: The underfunding of the water sector in Lagos is inexcusable. Owo wa (there is money.) The LASG generates humongous revenue annually from the Land Use Charge (LUC) and other state tax revenue sources.

The LUC is a source of IGR for Lagos State. In 2024, the state raked in N14 billion in revenue from LUC. It is a solid source of revenue with a progressive increase year-to-year. The revenue from the LUC is used to fund infrastructure and sundry municipal services, including public water supply. Advisably, the funding of public water supply must be adequately addressed and prioritised by the municipal government because water is crucial to health security, economic growth, environmental resilience, and is one of the determinants of people’s quality of life.

Both the legion of property owners and other taxpayers must, by right, ought to enjoy the benefit of the taxes they regularly pay to the coffers of the government on demand notices. Water, according to popular expression, is life! It is an essential commodity that should be made easily accessible and affordable.

The Lagos water supply could be a daunting task, but it is not insurmountable. The LASG should have the political will to act, while the management of LWC should NOT (my emphasis) continue to ignore a feasible solution hiding in plain sight.

By Tpl. Yacoob Abiodun, Planning Advocate, (+1) 718 307 9046