To mark World Neglected Tropical Diseases Day, a new report from the Strike Out Snakebite (SOS) initiative exposes a fragile frontline – as healthcare workers are battling broken systems that jeopardise both prevention and treatment of snakebite envenoming (SBE).

Snakebite is one of the world’s deadliest yet most overlooked Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), representing nearly half of the global burden of all NTDs and causing up to 138,000 deaths and 400,000 permanent disabilities every year. Despite this, snakebite receives only a fraction of the funding it desperately needs.

Snakebite envenoming is a crisis of inequality. It strikes hardest in rural communities – among children, agricultural workers, and families living far from health facilities. Victims often face long journeys to care, limited infrastructure, and costly and scarce antivenom supplies. These barriers turn a preventable and treatable condition into a life-threatening emergency.

As part of a new survey of 904 healthcare workers across Brazil, Nigeria, India, and Indonesia, findings from Nigeria revealed:

- 98% report challenges administering antivenom – the only WHO1-listed essential medicine for SBE treatment.

- 50% say their facilities lack full capacity to treat snakebite.

- 39% face daily antivenom shortages.

- 56% report poor infrastructure and inadequate equipment – raising the risk of limb loss, blindness and chronic neurological injury.

Elhadj As Sy, Chancellor of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and Co-Chair of the Global Snakebite Taskforce, said: “Too often, conversations on global health overlook those who shoulder the greatest burden: frontline healthcare workers. This report shines a light on the severe challenges they face in trying to save lives – and it is time to not just listen, but to mobilise. Many solutions exist, but we need political will and bold commitments from partners and investors to turn the tide on this preventable yet devastating Neglected Tropical Disease.

“Snakebite must no longer be overlooked or underfunded by the international community. It is time for action – not sympathy, not statements, but action worthy of the scale of this crisis.”

Antivenom is most effective when administered quickly – yet 82% of healthcare workers surveyed in Nigeria report life-threatening delays in seeking treatment, often due patient preference for traditional or alternative remedies (61%). Efficacy also depends on identifying the snake, but 42% report challenges administering antivenom due to uncertainty about the type of snake involved. The cost of delay is devastating: 43% reported avoidable delays ending in amputation or major surgery, potentially locking families into poverty and deepening inequality.

Simple precautions – such as wearing protective clothing and sturdy footwear, sleeping under well‑tucked mosquito nets, carrying a torch at night, and avoiding likely snake habitats – can signficantly reduce the risk of a bite. If a bite does occur, safely taking a photograph of the snake can help with identification and confirm treatment options, but only if it can be done without putting anyone at further risk.

To bring the report findings to life, a short film – Snakebite: from Science to Survival – has been released, featuring first-hand testimony from researchers, doctors, snake handlers, and survivors, underscoring the human toll and the urgency to act.

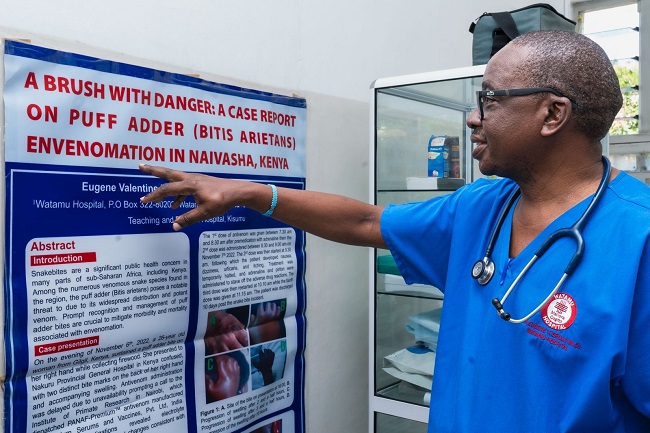

Dr Eugene Erulu from Kenya, who is featured in the film, said: “A snakebite is a medical emergency, and anytime it happens it needs to be dealt with urgently and with the right treatment. However, we know 70-80% of patients first go to the traditional healers, where they receive inadequate care. If you delay, you lose the patient, but this has never really sunk into the community.

“We must continue to educate the public on the importance of seeking care, alongside investing in local health systems to ensure all facilities have access to antivenom.”

Today, just two funders provide 65% of global investment into snakebite R&D, which is neither sustainable nor sufficient. Frontline healthcare workers in Nigeria are therefore calling for urgent investment from the international community – governments, global health leaders, multilateral agencies, philanthropists, and investors – to:

- Strengthen antivenom R&D (40%) and expand affordable, high‑quality manufacturing (43%);

- Improve data and monitoring (31%) and protective equipment (29%);

- Improve training programmes for healthcare professions (44%);

- Increase access to safe, effective antivenom (32%);

- Increase collaboration between governments, NGOs, and local health systems (31%)

- Improve access to healthcare facilities (24%), improve healthcare system infrastructure (16%), and scale community education (48%).

The solutions to end needless death and disability from snakebite already exist. By pooling resources to purchase antivenom and producing it in regional hubs, countries can stabilise prices and ensure a consistent supply of high-quality antivenom. Integrating snakebite prevention and treatment into national health plans will strengthen health systems and save lives.

Alongside this, investing in education, awareness programs, and preventative measures wantivenomer communities with the knowledge and tools they need to reduce risk and respond effectively when bites occur.

Strike Out Snakebite was launched in 2025 to drive action across four fronts: R&D, antivenom access, public health, and advocacy – aligned with WHO’s goal to halve deaths and disabilities by 2030. Its Global Snakebite Taskforce unites experts, funders, and policymakers to keep this crisis on the global agenda.

The moral imperative is clear: nobody should be dying from snakebite envenoming. This crisis is preventable, and targeted investment can catalyse significant impact. Now is the moment to act – and together, we can Strike Out Snakebite.