Now that a proposal to relax the prohibition on commercial trade in elephant ivory has been rejected – once again- at the latest conference of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, we have an extraordinary opportunity to chart a new and exciting path for elephant conservation across Africa.

Collectively we have over a century of experience, working to understand elephant ecology and conservation, in defining and regulating sustainable trade, and in developing plans and policies to protect wildlife. We believe African elephant range states should now harness a broader suite of policy tools to finally provide the protection and generate the financing this keystone species deserves.

On November 29, 2025, the overwhelming majority of countries at the CITES conference voted against the proposal by the southern African nation of Namibia for the ivory trade ban to be partially lifted so its government could sell its stockpile of ivory.

We were pleased to see that delegates from most African countries, and the majority of other countries across the world, did not want to put at risk the huge progress made since 1990 when CITES banned commercial trading in African elephant ivory; and similar resolutions have been rejected at the last three CITES gatherings. The evidence from previous partial exemptions to the 1990 ban is clear: a trickle of legal trade leads to a deluge of elephant blood as poachers target the animals for their white gold.

However, as former politicians and policy makers who have had to balance environmental, economic and electoral concerns, we understand Namibia’s predicament. Its great achievements in conservation and in protecting elephants across its territory, are hugely expensive, and resources are tight. But the true value of elephants is not in their ivory, and the short-term financial benefits of sales are not the answer.

As so often in public policy the key here is “monetising”: creating value out of an asset. For too long the sole focus for creating value out of elephants was through selling their tusks. A high price for ivory has always led to a surge of illegal killing, illegal trade, and laundering.

This trade resulted in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of elephants, in Africa’s savannas in the 1970s-1980’s and subsequently in the forests, between 2007-2015. The second wave of killing resulted in the loss of upwards of 70% of forest elephants.

Elephant poaching is generally carried out by transnational criminal networks. It undermines governance and security, degrades ecosystems, and destroys sustainable, tourism-based economies. Furthermore, the forest elephant in particular is a critical part of the Congo basin rain forest ecosystem.

An elephant is a remarkable value-adding creature, working as an unpaid landscape architect. It leaves in its wake a trail of environmental benefits: its dung, the seeds it spreads, the soil it shifts, the biodiversity it catalyses, the tree species distribution it impacts, the winnowing out of less carbon absorbent plant life, the boosting of the above-ground biomass.

And this rich, valuable, transformative trail does not just run for thousands of looping kilometres during an animal’s life. It has an impact long after each individual animal has died.

Those of us who have spent time in the Congo basin can tell the difference between a forest with an active elephant population and one without. The level of life, of insect activity, the shape of the trees, even the light itself, is the difference between a full colour photograph and one in black and white. You might not see the forest elephant – they are famously good at ghosting away into thin air – but you see their rich impact.

Scientifically, there is research that suggests, for example, that a single forest elephant drives carbon capture increases worth $1.75 million. That is one helluva a landscape gardener!

This figure alone is extraordinary. Like all good science, this research begs more questions, demands more work, opens more avenues to explore. We need similar research on African savanna elephants that inhabit more open, grassland environments, not least in Namibia. But even if this figure is proven to be out by an order of magnitude, the value to the planet of an elephant alive is unequivocally and demonstrably many times more than its value dead as a source of ivory.

Furthermore, elephants are the biggest attraction of Africa’s wildlife tourism industry, estimated to generate over $30 billion annually and to employ over 3.5 million people.

History has taught us the high costs of reopening the commercial trade in ivory. Instead, let us forge a different path, working with Namibia and all elephant range states, and find creative ways to monetise the many benefits we derive from these magnificent animals.

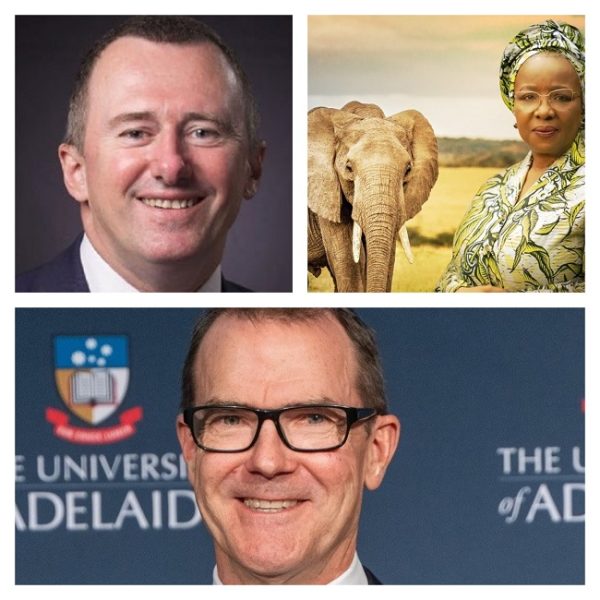

By Professor Lee White CBE (Trustee of the Elephant Protection Initiative Foundation, a pan-African alliance of 26 nations working to protect the elephant population and former Minister of Water, Forests, Sea and Environment of the Gabonese Republic), John Scanlon AO (CEO of the Elephant Protection Initiative Foundation and former Secretary General of CITES) and Sharon Ikeazor CON (Chair of the Elephant Protection Initiative Foundation and former Minister of State for Environment, Federal Republic of Nigeria)