In 2020, Ahmed Jibril left his home in Niger Republic and crossed into Nigeria with a herd of over 60 cattle. Like many other pastoralists from the Sahel, he was driven by a familiar challenge: the worsening impact of desertification, insufficient rainfall, and dwindling pasturelands. But, unlike many stories marred by farmer-herder violence, Jibril’s journey took a turn toward peaceful coexistence and mutual benefit.

Jibril’s first stop was Bokkos Local Government Area of Plateau State in Nigeria’s North Central region. However, rising tensions and violent clashes between herders and farmers forced him to continue his migration further south. Eventually, he found a welcoming host community at Nkaleke Echara, a rural community in Ebonyi State, South-East, Nigeria.

At Nkaleke Echara, Jibril has built a symbiotic relationship with his hosts. While his cattle provide the community with a steady supply of affordable beef and fresh milk, the farmers gain organic manure from cattle dung, which enriches their soil and improves harvests.

“We used to come to Nigeria only after the harvest and return before planting season,” Jibril recalled, describing a rhythm of migration now broken by climate change and conflict. “But things have changed. We move farther and stay longer.”

What Numbers Say about Herders Movement

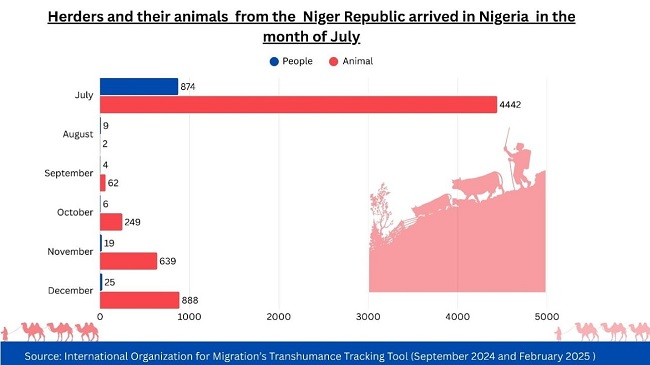

Jibril’s journey mirrors a larger migration movement monitored by the International Organisation for Migration’s Transhumance Tracking Tool (September 2024 and February 2025 reports). The reports paint a broader picture of this movement across borders. Between July and December 2024 alone, 937 herders and 6,282 animals migrated from Niger Republic to Nigeria. The highest volume was recorded in July, accounting for 93% of the human and 71% of the animal movements during that period.

While most herders and their livestock are headed to northern Nigerian states, with Jigawa State topping the list, a small but growing number, like Jibril, continue their journey southward in search of more sustainable grazing land and safer environments.

Stories of Symbiosis

Despite the common narrative of farmer-herder conflict, there are several communities where cooperation flourishes. One such example is Dawaki Kapil in Kanke Local Government Area, Plateau State, where a mutually beneficial relationship has been existing between the natives and the migrant herders for decades.

Each year, especially after the harvest season, the community welcomes migrant herders who are allowed to graze their herds in fallow land in exchange for manure. The number of herders and their cattle that go to Kapil on seasonal migration varies depending on the grazing condition. However, in the past two years, the community has been hosting 100 to 150 herders and about 20,000 cattle annually.

“Their animals feed on our dry stalks and crop leftovers, while their dung replenishes soil nutrients, helping us prepare for a more productive next season,” said Mr. Lucky Shekara Kapil, a youth leader of Kapil village.

The arrangement goes beyond soil fertility. Some farmers partner with herders on cross-breeding programmes, improving the quality of local livestock.

At Kapil, some farmers lobby migrant herders to graze on their fallow lands, marking a significant shift from the hostility seen elsewhere.

Economic, Environmental and Health Incentives

In the South-East, where Jibril currently grazes his herds, herders have become a permanent presence. Alhaji Bello Maigari, Leader of Nomadic Fulani in Anambra State, estimates there are over one million herders and their animals in the region. While exact data on international migrants is unclear, he notes that many herders have settled in Southern Nigeria for decades, drawn by not just greener pastures but also health and market advantages.

According to Maigari, one major reason for the southward migration is the reduced incidence of Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (CBPP), a deadly livestock disease common in the Sahel.

“The South is safer for our cattle. They are healthier here,” he said.

But health is just one factor. Economics plays a bigger role. In the South-East, especially, cattle have become a cultural symbol of status. During burials, weddings, child-naming ceremonies, and birthdays, showcasing live cattle is seen as a marker of wealth and prestige. This consistent demand creates a strong market for herders, who can earn significantly more in the South than in the North, and perhaps in other Sahel regions.

A New Model for Coexistence?

While the risks of violent farmer-herder clashes remain real and urgent, the experiences of Jibril in Nkaleke Echara and herders in Dawaki Kapil offer a glimpse of what’s possible when migration is managed peacefully and relationships are built on mutual benefit.

As climate change accelerates and pastoral migration becomes increasingly inevitable, these models of coexistence may offer valuable lessons, not just for Nigeria, but for the broader Sahel region grappling with similar challenges.

“If there is understanding, both herders and the farmers can live peacefully and share our mutual benefits,” Jubril said in reflection.

By Inya Agha Egwu and Michael Simire